Medicinal Colour

The presence of colour in even the most dilapidated spaces can transform our minds for the better.

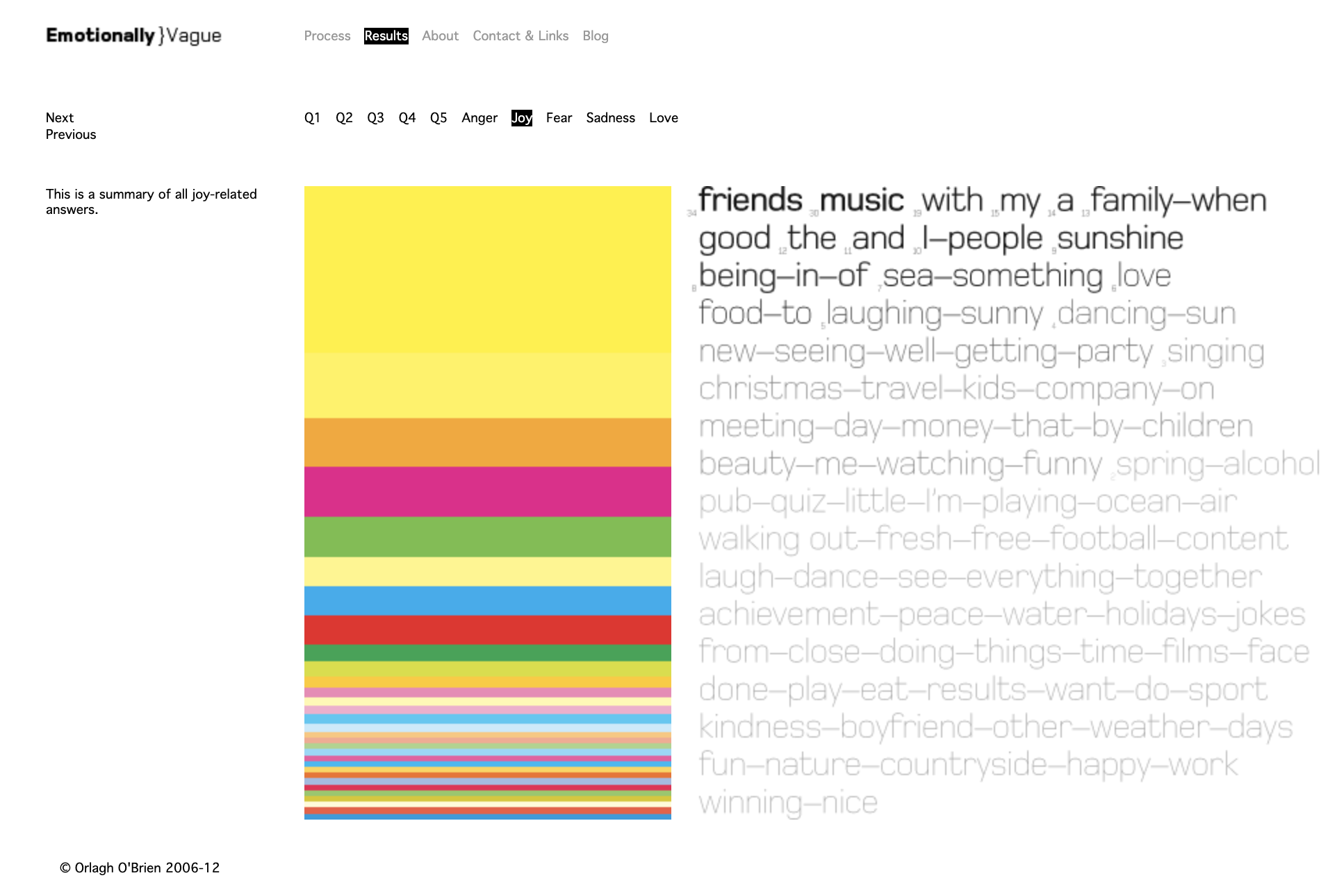

Inspired by the Joy palette from the study, found here

The data found here. And yeah this data shows a LOT of yellow, but I’m not that committed to science, I really liked this version of the Donkey Ear succulent plant I rendered.

Colour and why you need every bit of it

There’s data to back up the good feelings you get when you see brightly coloured balloons, walls, and clothing. From our earliest memories, children’s toys are in highly saturated colours. We are surrounded by these energetic hues, and we form connections to these swatches, but later in life, “when we grow up” that colour is often diminished. Have you noticed how colourful kindergarten classrooms are? Humans also learn more in a colourful classroom. So why, then, are our higher education spaces, and workplaces so drab?

In Western culture, neutral sophistication is prioritized over colour. In the 1800s a cultural response was written implying that only “savage nations, uneducated people, and children have a great predilection for vivid colours […] that people of refinement avoid vivid colours in their dress and the objects that are about them, and seem inclined to banish them altogether from their presence.” - J. W. Goethe (1840). In South America, and Asia, cities are often full of colourful buildings, marketplaces, and office buildings. In North America, we tend to lean towards chromophobia.

Edi Rama, winner of the City Mayors World Mayor 2004 contest, to the mayor’s office in Tirana, the capital of Albania infused his once crime-ridden, unsafe city with bright colour. Broken by decades of repressive dictatorship and starved of resources by ten years of chaos after the fall of Communist rule, by the late 1990s Tirana was in a poor state indeed. Public services left much to be desired and sometimes rubbish piled uncollected in the street. Tax evasion was rife. As Rama himself has described it, “The city was dead. It looked like a transit station where one could stay only if waiting for something.” The painted buildings were an act of desperation by a mayor faced with an empty treasury and a demoralized populace.

At first, the reactions were mixed: some citizens were horrified, others curious, a few delighted. But soon after, strange things began to happen. People stopped dropping litter in the streets. They started to pay their taxes. Shopkeepers removed the metal grates from their windows. They claimed the streets felt safer, even though there were no more police than before. People began to gather in cafés again and talked of raising their children in a new kind of city. Nothing had changed, except a few patches of red and yellow, turquoise and violet on the surface. And yet everything had changed. (Full article here, by Ingrid Fetell Lee)

”While we think of colour as an attribute, really it’s a happening: a constantly occurring dance between light and matter. When a beam of light strikes an object, let’s say a multicoloured glass vase, it is pelting its surface with tiny energetic particles called photons. The energy of some photons is absorbed, heating the glass imperceptibly. But other photons are repelled, ricocheting back out into the atmosphere.

These photons, landing on our retinas, create the sensation of colour. The specific hue we see has to do with the energy of the photons — high-energy, short wavelengths look blue to us, while low-energy, long ones appear red. The brightest pigments tend to have a more “excitable” molecular structure. Their electrons can be disturbed with very little light, making their colours appear intense to our eyes.”

(Full article here.)

“ Deep within us, we all have this impulse to seek out joy in our surroundings. And we have it for a reason. Joy isn’t some superfluous extra. It’s directly connected to our fundamental instinct for survival. On the most basic level, the drive toward joy is the drive toward life. ”